Living on the Front Line

I’ve been putting together a compilation CD for Finbar’s 17th birthday. Finbar is the son of a friend, and for the last couple of years, he’s come with Your Dad to Pilton. He’s a metallist by inclination, and I’m so not, and I keep bombarding him with CD’s of the kind of old nonsense I listen to, which I in my wisdom think would be improving for young rockists. It’s hard to know where to stop. For instance, should I share with a 17 year old metal guitarist my ridiculous Jimmy Webb thing?

Common sense says no, as does previous experience of trying to persuade today’s youngsters that what they listen to is just noise, but that in our day, we had proper songs. Sometimes though, dessicated hipsters can still get it right. A few years back, Minnie was right into her first generation punk, and I bought her a Cd of the old Front Line compilation, telling her that reggae was what punks used to listen to between bands at gigs. I don’t know if she listens much to punk anymore; but she still listens to reggae.

The first Front Line compilation came out in 1976 on a Virgin off-shoot label, and for lots of people, me included, it was a first stop after Bob Marley, one which turned on a new generation to Jamaican music.

By 1976, a few pals and I had been going to The Reading Festival for several years. The fact that that year’s line up was almost terminally weak would not deter us from going, not in the least. It had, after all, been a long hot summer; and my pals and I had just left school. The Front Line album had been part of the soundtrack to that extraordinary time. We’d started the summer by going to see the Beach Boys, and were ending it by going for a weekend of revved up teenage hedonism.

The only bands I was interested in seeing were Eddie and the Hot Rods; and, on the Friday night, from Front Line Jamaica, U-Roy and The Mighty Diamonds. My pals and I went down to the front ready to rocksteady. But this was 1976, and the crowd were not ready for reggae at Reading . If memory serves right, there were about 500 people at the front, and 29500 people behind us screaming racist abuse and throwing beer cans, both at the artists on the stage, and at the small band of enthusiasts at the front. It should be remembered that in those days, there was only one stage, so all the festival goers sat in front of the main stage. The rockists didn’t like reggae at all. They didn’t really like black people, it seemed to me. They liked what they liked; Pink Floyd, Uriah Heep, The Enid etc. And they were prepared to stone anyone who liked anything else to death.

Cans rained down on the stage and what would now be called ‘the mosh pit’, streaming beer as they came over. We were towards the back of this area, and it was scary, nasty; exhilerating, modern. You knew you were on the side of the angels, and it’s not often you can say that. I still remember the faces of hatred on the hippies who screamed abuse from yards behind our heads, while we tried to pay the ultimate complement to the bands by dancing.

A few months later, when I met Old Perry Venus for the first time, I learned that we could have met that day, as he too was one of the 500. We had taken a turn at a cultural front line, and we’re still proud of being there that day. There are probably a few hippies who now dance to countless reggae bands at festivals every summer, who have let the memory of whose side they were on in 1976 grass over.

Then my friend Pete Smith the Blacksmith came round this afternoon, and we got to talking about how front lines can turn into backwaters. From my study window, I look down on the central crossroads in Presteigne; in 1645, there was a firefight at this crossroads, 50 metres from where my flat now stands, as Parliamentarians and Royalists skirmished through the town. Also from my study window, I look across the Lugg valley to the ruins of Stapledon Castle; from my bedroom, I can see the old castle mound here in town, now called The Warden and given over to dog walkers. The two castles faced one another across doubtful territory, long fought over. There were at least two major battles within an eight mile radius of here; Pilleth and Mortimer’s Cross . The battle sites are grassed over now, and all but forgotten. Offa’s Dyke, the fortification which seperates England from Wales comes within three miles of the town; the long-distance footpath which runs its length now brings welcome tourism to Radnorshire. The old Radnorshire Militia building, Garrison House, is now painted a peaceful pink, and has wisteria round the door.

For hundreds of years, this was the front line. And now it isn’t. I guess It’s no compensation to those hundreds of thousands of people who are currently living on front lines to know that peace can come, even if it takes another several hundreds of years to arrive.

But it has to be good news, surely, that front lines of all kinds grass over?

Ah well, different shit, same year. Or something like that. Or the total opposite. I got ripped off of £30 by a couple of bogus DS with a big stick that year. Thinking…

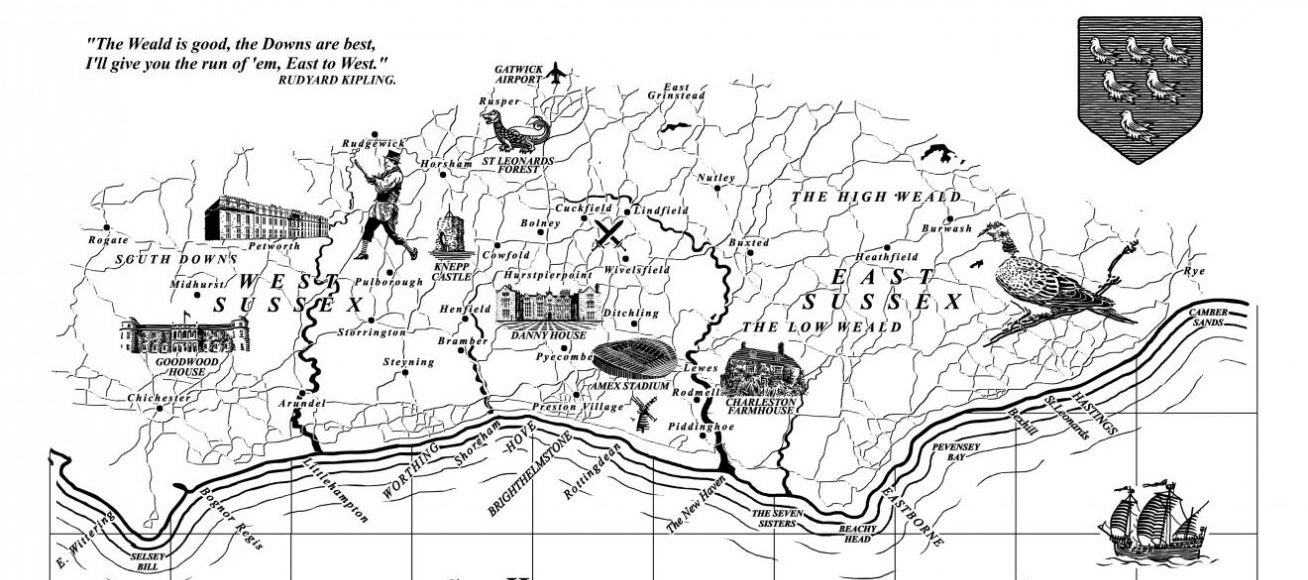

I remember one night at Suusex University at one of their all nighters, just as the dawn was breaking over Falmer, me and a handful of chums decided to pool our illegals and celebrate the rebirth of the eternal dawn in a blaze of mental fuzziness. There were tabs, bits of green stuff, some powder, the scrapings from Tall Barry’s sole and possibly some discarded body parts. Or at least a fragment or two of ear wax. They were all mixed up in a half beaker of flat beer and Tall Barry decided to be the first to try it, but thought it would be a wheeze to filter it through one of his socks. This is where I developed my love of cookery.

Wow. Perfectly preserved Duck Decoy. That’s the sort of thing that makes life so great!

I’ve pimped you on my site, by the way. Even rearranged my modules to make you prominent.

Love…

No, Graham, no. Your memory has been addled by all the amyl nitrate we snarfed up in the tent. Quo was ’78, the last year I went to Reading. I got threatened and roughed up for my cricketing outfit by some members of the Quo Army, who were offended by somebody wearing a tie at a festival.

Ian my love. I was there with you. It was the Quo Army, lowering in the distance like a storm front. They threw cans and bottles of urine at us. They knocked each other’s teeth out as a show of affection. John Peel asked for a show of peace love and understanding but they didn’t inhabit the same biosphere as us. Was that the year Patti Smith played?

Love,

Graham

In the clip of Your Dad at last years’ Glasto, the audience member is Matthew Barnard, a great and good man, who we met during The Longest Crawl on the boat from Aberdeen to Lerwick.